Francisco Castaño Sr., Forefather of the Freedome®

For 31 years, Geometrica has built strong, energy-efficient structures around the globe. But we didn't pull geodesic design out of the sky. Our expertise is due, in large part, to the pioneers of gridshell technology.

Among them is Francisco Castaño Hernandez, a Mexican engineer who initially specialized in building concrete shells in the 1960's, and then broadened the horizon to metal gridshell technology. Following the convention for Spanish names, Castaño is his father's surname and Hernandez is his mother's maiden name. This article refers to him as Francisco Castaño Sr. to distinguish him from his son, Francisco Castaño, CEO of Geometrica.

Castaño Sr. was the first to realize the potential for free form and long span in gridshell design. Many of the projects he built are architectural icons even today, including the Palacio de los Deportes, the atrium dome at Archivo de la Nación, various hyperboloid water towers, and the Rio 70 theater, among others.

Geometrica domes, barrel vaults and long span structures have taken gridshell technology to new heights all over the globe, thanks to his pioneering efforts.

Palacio de los Deportes in Mexico City

Early Years

Francisco Castaño Sr. was the eldest of six children. His interest in engineering was kindled by his father, an engineer who manufactured cabinetry and light equipment support structures out of sheet metal for use in industrial laboratories and kitchens. In his father's factory he became familiar with the extremely slender forms common in sheet metal. This exposure gave him an invaluable intuitive feel for thin surface buckling phenomena. During his civil engineering studies in the fifties he was inspired by the works of Candela, Torroja and Nervi. He wrote his professional thesis on the design of hyperbolic paraboloid shells in reinforced concrete.

For a few years after graduating from Monterrey Tech, Castaño Sr. worked for large construction firms designing and building hyperbolic paraboloids "umbrellas" in concrete for factories and exhibit spaces, and occasionally invited his young wife, Reyna García, to enjoy the breeze atop these light constructions.

Reyna Garcia enjoys the breeze atop a hypar.

In the early 60s, Castaño Sr. met the Fentiman brothers, who had developed a compact joint to build aircraft hangar doors as "space frames." He saw the potential to use such joint to build gridshells, and launched his own company in one small room inside an apartment in Mexico City. His idea was to apply the "space frame" technology to enable the forms envisioned by the concrete shell pioneers. In fact, Castaño Sr. was able to merge these two budding technological advances and lay the early foundation for today's Freedome®. He quickly realized the huge advantages of expressing structural form with a lattice of circular tubular sections. It was as if the colossal roofs he designed were lighter than air and seemingly tied down to prevent them from flying.

In 1964 he erected the first such gridshell hypar in Mexico City. Designed by Architect Carlos Contreras, the diamond shaped roof was supported on the two closest corners and cantilevered 14 meters in each of two opposite directions.

Double cantilever auto dealership

From Monterrey to Montreal

A premier test in Castaño Sr.'s career came in 1966 when he was charged with the design and construction of a beautiful multi-leaf hyperbolic paraboloid for the Mexico pavilion at Expo '67 in Montreal. The architects were A. García Corona and L. Fabela. The engineering was by Castaño Sr. and Dr. Douglas Wright, then heading the Civil Engineering department at the University of Waterloo.

That this would be an incredible challenge for Castaño Sr.'s company was evident from the start. To avoid building in the harsh Canadian winter, most of the 120 countries exhibiting had almost finished their facilities well in advance of the opening of the fair in April. But Mexico did not award its contract until a few months before opening day. In order to meet the crazy schedule, the structure would be prefabricated in Monterrey and trucked to Montreal. Forty trained Mexican workers would mount the pavilion according to Castaño's newly adopted design. The Mexican building team was thrilled to earn Canadian wages plus expenses, including winter clothes, meals and lodging. Construction started on an optimistic note in September, as the mild summer turned into a colorful fall.

Chaparro Garcia raised the flag.

Then the weather turned, as it was prone to do above the 45th parallel. The workers, used to the dry desert heat of Monterrey, now experienced the full force of the bitter Montreal winter. Tortillas would get cold even as they cradled warm filling, giving a whole new meaning to crunchy tacos. Tears, ears and rears froze — a particularly unpleasant scenario 60 feet above ground! But work they did.

On the coldest day that winter, the thermometer hit -40°C. Construction activity on all buildings stopped. Just then, José "Chaparro" García, a welder and natural leader in the team, climbed atop the highest hypar leaf, welded a flagpole to it, and raised the Mexican flag to his colleagues' cheers. With renewed spirits, the Mexican crew finished construction a few weeks later, just in time for the Expo. Mexico's exhibit opened to general acclaim. Castaño's company's reputation soared.

The Mexican Pavillion at Expo '67, Montreal, Canada

Growth and Innovation

Design and fabrication of gridshells requires exacting calculations, measurements, jigs and tools. It is difficult enough these days with high-speed electronic computers. But back in the 1960s, "computers" were people, and the design of arbitrary forms was beyond imaginable. Castaño Sr. developed a system of design that involved laying out parallel pairs of coordinate maps representing a gridshell's geometry.

Metarsa Factory, Ricardo Sein, Architect

Each map was drawn on a "blanket" of paper that was often 10m2. Using mechanical calculators, slide rulers and tables of trigonometric, algebraic and logarithmic functions, human computers would tape coordinates on the geometry blanket, then calculate lengths, cut angles, twists and other fabrication parameters for each of a gridshell's components.

The Rio 70 Cinema still entertains movie-goers today.

To achieve the volume of calculations Castaño Sr. required, the recruited "computers" often went beyond himself and employees, to friends, wife and children. Everything was done twice, once on each of the blankets. The results were then tabulated and cross-checked thoroughly. Despite the limited technology, the whole process would have aced a modern ISO 9001 audit. The resulting forms were revolutionary, including hypars, geodesic domes, freeform shells, hyperboloids of revolution. Projects streamed in: Multiple cinemas, arenas, exhibit halls, shopping centers, zoo enclosures were built in metal gridshells.

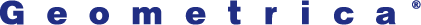

At a tradeshow, late 1970s.

The City Auditorium, for Toluca, Mexico, was the very first free-form gridshell. Completed in 1968, it won that year's national design award for architects G. Gallo and A. Azorín.

Toluca Auditorium

Castano Sr.'s concrete background came in handy as he design efficient elevated water towers. The gridshell became scaffold, steel plates provided tension strength and concrete formwork, and concrete provided compressive strength in an innovative hyperboloid of revolution geometry. Castaño, Sr. planted dozens of his tanks in almost every state of the Republic of Mexico. Some soar higher than 10-story buildings, with capacities of up to 4 million liters of water.

Water tower

Another first came in using domes to store bulk materials. He first applied this technology to store grains and aggregates in volumes previously undreamed, starting a business line in which Geometrica has thrived to this day.

Avicultores sorghum silo, 95m span

World cup's Puebla stadium

Arrangements of hyperbolic paraboloids were used for the Olympics and World Cup venues. Castaño Sr. collaborated with Dr. Douglas Wright on the design of a large concert hall in Ontario, on Candela's hypars for the Sports Palace in Mexico City and on several other projects. Even after 45 years, in 2013, Geometrica's entry of the Sports Palace won the American Society for Quality "Quality Lasts" competition.

Palacio de los deportes

Legacy

Construction is a team effort. Architects, engineers, contractors and suppliers act in concert to realize complex facilities that serve owners and occupants alike. Architects direct the team by providing the vision of the building. Engineers and contractors land the vision using available technologies, or developing new ones. These last bits are where Castaño Sr. made his contributions.

(Left): Dr. Douglas Wright and Francisco Castano Sr. (Right): Harold "Bud" Fentiman, Reyna García and Francisco Castano Sr. c. 1984

Not directly under the spotlight, his works of engineering and construction nevertheless enabled the bold, award winning visions by renowned architects such as Candela, Gallo and Azorin, García Corona and Fabela, and many others.

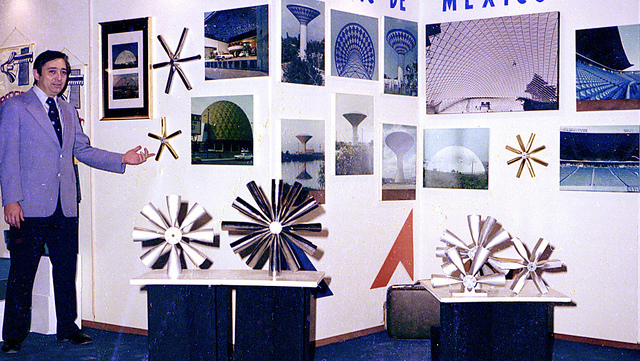

Later in his career, in the Third International Conference on Space Structures, Castaño Sr. was recognized by the Space Structures Research Center at the University of Surrey in England as a "Special Pioneer." This award recognized his "outstanding contribution to the development of space frame structures." Co-recipients of the award were Dr. Max Mengerinhausen, Prof. Yoshikatsu Tsuboi, Dr. Stéphane du Château, the Fentiman brothers, Fujio Matsushita and Don Richter.

Castaño Sr. suffered illness that forced an early retirement and prevented him from continuing his work in his later years. But his greatest tribute was his family. He was inspired and supported by his wife, Reyna García, who outlived him. She often played a part in the realization of the structures, and enabled her husband to pursue a global career as she raised their four sons and a daughter. She still entertains a vast network of children, grandchildren and relatives in her home in Mexico.

Their sons, Francisco and Roel, followed in their father's footsteps and continue to expand upon his innovations. They founded Geometrica in 1992, and today, the company continues to provide technology that inspires architects and designers to realize bold visions. Geometrica structures have been built in over 40 countries for a variety of applications including environmental protection, sports stadiums and museums. Innovations continue in several fronts, including structural geometry, an improved joint, new software and wiki-based quality management.

Through the years dome technology continued to evolve and led to the Freedome® — Geometrica's trademarked free-style dome. As circular domes, Freedomes may have lamella, Lace™ or Saturn™ in-surface patterns and single or double grid layers. But these structures can also be designed with a non-circular plan, bringing complete design freedom to architects and engineers the world over. Using the inherent strength of doubly curved surfaces, Freedomes can clear spans up to 400m (about the length of four football fields) on any terrain, including brutal mountainside slopes or areas with an irregular shape requiring a nonconventional enclosure.

The question is, "What can Geometrica build for you?" To learn more, please fill our inquiry form.